Year: 2007

Rube Goldberg-inspired show

Looks like Discovery US has a series coming up in which a team of engineers (/designers/etc) build ridiculously complex machines to do something trivially simple. That is, a ‘Rube Goldberg’ machine, or – as we say in the UK – a ‘Heath Robinson’ machine.

It’s been done before, of course. Notably by Fischli and Weiss in ‘The Way Things Go,’ but also as a TV gameshow, most recently in BBC4’s Simply Complicated. That show suffered the classic problem of these ‘chain reaction’ machines: unless they’re incredibly carefully-designed, they’re impossible to catch on camera, and the viewer is left baffled rather than inspired.

I banged on about this a year ago in relation to the ‘Diet Coke & Mentos Experiment II’ film, and for my money the best video realisation of the concept still lies not with the Honda advert, seminal as it was, but with the Japanese children’s show Pitagora Suichi, clips of which you’ll find here. Over the years their team has clearly got it down to a fine art.

It sounds like the Discovery series is going about things the right way, at least, in that there’s no hint of a competition – rather, the team they’re casting sounds more like ‘resident engineers.’ I hope that’s the case, because if it is, they might have a fighting chance of getting the shots they’re after. But they’re still facing a very steep learning curve, particularly if they’re using engineers who look good on camera, but have no experience of working with the things.

If I was at the World Congress of Science Producers in New York this week, I’d be asking Discovery myself.

[via Boing Boing]

What is television for?

Peter Fincham (ex- Controller of BBC1) asks his (former) peers, via the Guardian, what television is for. Which is what Paxman asked in his MacTaggart lecture at Edinburgh this year. The replies make for depressing reading.

Not because the respondents are wrong, nor thoughtless. But rather because their replies are careful, considered, enthusiastic, and positive. They say exactly what one would want them to say; that television is there to entertain us, yes, but also to challenge, inspire, fascinate, surprise, and so on.

We also know that commissioning editors talk the same language – they actively seek the challenging, the offbeat, the radical.

So… where does it all go wrong? How can these thoughtful and capable people end up producing the schedules we see, and the programmes we moan about not wanting to watch?

The answer, of course, is that it’s often not the programme-makers that pick the dross, it’s The System. And I mean that not in a buck-passing way, but in a really big way.

The System of TV goes like this: Thou Shalt Make Money (commercial channels), or else Thou Shalt Make Relevant Programmes (public service). In both cases, The System grades the results by means of ratings. That is, the only measure of success is sheer bulk of audience.

Commissioners can rail against this all they want, but if they don’t deliver ratings winners, they’re out. Such is the reality of a mass audience medium; the mass audience is what matters, and thus we – the mass audience – are collectively to blame for all the ills of The System.

If we didn’t watch the dross we subsequently complain about, it wouldn’t get made. It really is that simple.

There are, as I see it, only two solutions to the problem of The System:

- Switch off. Simply don’t watch the stuff you don’t like. The System will notice in the end, if you hold your nerve and enough people do it.

- Find a different way of measuring impact.

I’m slightly surprised that, for all the interactive TV escapades of the last ten years, I’ve never seen a channel-wide ‘please rate the programme you just watched’ feature. And let’s not even get started on, say, having the red button text your mates to let them know what you’re watching.

Can TV learn from Digg and Twitter? Hell, yes. Moreover, it has to learn, and fast, or the people who know how to game The System will take over from Fincham’s respondents, the ones who know how to make the TV we actually want.

Personally, I fear it’s already too late.

Weird Leopard thing #436

Why does Quick Look not work in file open/save dialogs?

World Beach Project

The World Beach Project – head to a beach, do something with stones, take pictures, bung ’em on a Google Map-based site run by the V&A.

OK, I paraphrase somewhat. Really lovely simple concept, some gorgeous pebble arrangements, and one of those ‘cobbled together with existing bits of web-tech’ executions of which I rather approve.

Via Flossie (who wants to do something similar with stories), via John Coombes, of this parish.

With fame comes Subversion

Last week I was mostly:

- Working out how to introduce scientists to the concept of narrative, without them running a mile, and:

- Building a little blog in Movable Type.

In the course of the latter, I posted here a few times and also left some comments and queries on the Movable Type forums. They’re basically deserted, to the extent that I’ve had a post brewing titled ‘Where are all the Movable Type users?’ Seriously – where are they? Apart from people building entire newspaper sites in MT, it’s rather hard to find anyone talking about it. Which is… worrying.

So anyway, I posted about stuff here, and since I accidentally deleted the comments sidebar widget the other day you probably don’t know that people showed up and told me helpful things. People like Byrne Reese and Tim Appnel, respectively Product Manager for Movable Type and MT community developer/documenter. Rrrrright. OK. Then, off the back of that, I had a couple of emails asking me for help and advice on MT, since I apparently know what I’m talking about. Uhh… I’m sorry, what?

In the back of my mind through all this has been what I might do with The Daily Grind here. And what I might do, currently, goes like this:

- Reimplement the MT default templates using the Blueprint-CSS grid framework.

- Apply some of the stuff from here. In particular, some of this stuff I tried to do in the old Daily Grind typography, but manifestly failed, perhaps because browsers didn’t implement the crucial bits at the time. The sibling selector stuff is very close to magic, if you ask me. Which perhaps reveals how little I truly know.

- Sprinkle comments through the template code and CSS so people can actually hack on this.

- Build the new Daily Grind off that basis.

Trouble is, if I do all this I’m rather concerned I might have a useful little open source project on my hands. And I’m really not ready for CVS/Subversion/Git/Google Code/etc. Dang.

Perhaps I should explore Habari instead…

Daft hands

Genius video. This is, I think, what YouTube is for.

(via Tom Coates → Kevin Marks → Kevin’s Twitter → Kevin’s Facebook status. Which chain probably accounts for a goodly proportion of the 8.6 million views the thing’s had on.)

For the record

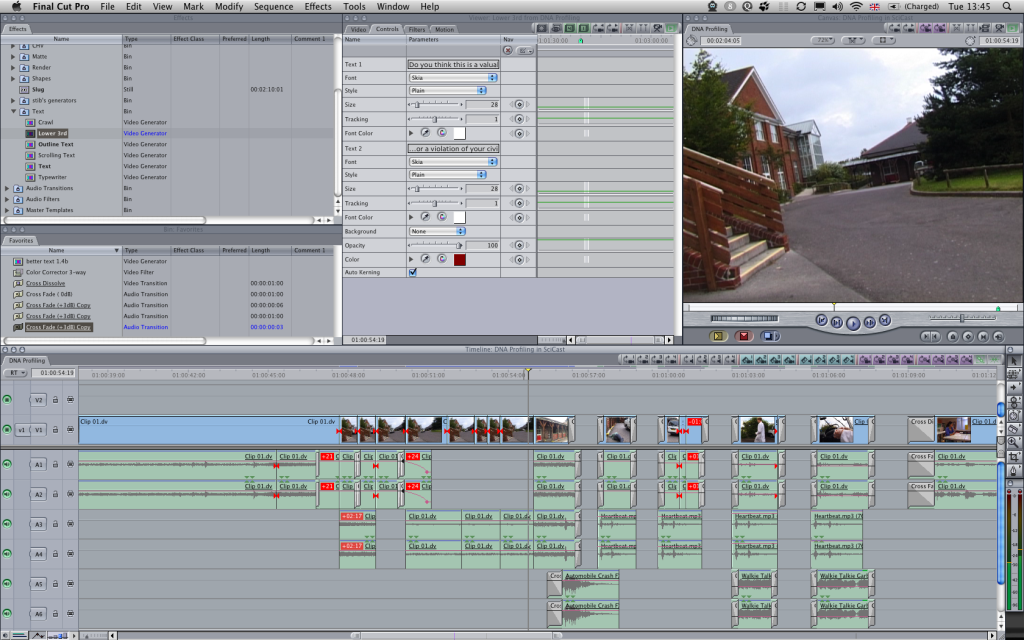

It’s a horrid, foul, freezing, rainy day in Glasgow; I’m vision-mixing a lecture I must have seen five times now; and yes, I know there’s more than one thing screwy with my RSS.

That is all.

IE7 inspector add-on

Blimey! Google might not know about it (not that I could find, anyway), but Microsoft have an inspector add-on for IE7. I’m using it now in an attempt to work out why the &%&£ IE is barfing on some sub-pages but not others, and why it’s ignoring .asset-heading a:visited when Safari and Firefox are both doing what they’re told.

[update: of course, the inspector is telling me that a specific element is set to display as white, with no text decoration. When it’s actually showing as grey and underlined. Huh]

Talking rubbish

After a year of talking about talking, on Wednesday I talked at Strathclyde Uni under the title ‘Science on Screen.’ There was some confusion about the audience: I was expecting about 40 who’d previously done a science communication module, but thanks to a bit of a mix-up it seems basically nobody received the notice, so I ended up with about eight random post-docs.

Hmm. ‘Less of a lecture and more a fireside chat, then,’ I thought, as I frantically deleted slides.

So I didn’t get to pinch Christopher Booker’s genius comparison of the opening of Gilgamesh with Dr. No, and I didn’t get to use that as a lead-in to discuss the philosophy of science in the context of narrative theory (in ten minutes). Which is a shame, because now that I’ve done the rest of it, I think it might actually work. When I was writing the talk it felt like a ridiculous exaggeration of how media professionals think – but actually, I think it’s the stuff we pick up as we go along, and hence take for granted without even noticing.

Dropping it on post-grads would have been fun. I did retain a bit describing the five-act structure and Robert McKee, and hence ad-libbed my way through an example of why all Horizons are basically the same. Which got a gratifying number of laughs as I did it, and a couple of ‘woah!’s. Which was nice.

My developing thesis goes something like this:

- There are lots of science engagement projects out there, but too many of them are unsophisticated, ignore best practice, and suffer from low impact.

- This is partly because working scientists don’t realise ‘science communication’ is a discipline in its own right, with Stuff to Learn. And when they see it, they don’t recognise it, because science communicators often aren’t very good at being clear about what they do either.

- Dropping a mad lump of communications theory on scientists can actually work, in that it jolts them out of assuming it’s all straightforward – hence my slide on narrative theory, and trying to frame that in terms that make sense to scientists.

- If done right, I think this may be a way of explaining to scientists what media people mean when we ask ‘Yes, but what’s the story?’ – which in turn I think leads to better, more engaging, engagement projects.

- There’s a convenient model for ‘proper’ storytelling in science already – the lecture demo. We all recognise them when we see them, and analysing them as five-act stories (yes, really) helps explain why some are more satisfying than others.

- Thus, when it comes to short web films, science is in a really strong position, because we already have this vast catalogue of suitable material. I can’t think of another subject that does, actually.

- Hence: SciCast. Hurrah.

In most circumstances it won’t be appropriate to cover this stuff, which is a shame, because it’s fun but also feels like it’s actually useful. Which I wasn’t really expecting when I started down this route, on Tuesday. Somewhere since then I must have had a turning point.